/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/70946952/GettyImages_566014179.0.jpg)

Over the last 20 years, eating locally produced food has become synonymous with eating more ethically, healthily, and sustainably.

Locavorism has been touted by popular food writers, local governments, think tanks, and big environmental nonprofits, sold as one clear change that could help to heal our ailing, industrialized food system. It would do so by revitalizing local agricultural economies, supporting small farmers, getting more nutritious and fresher products to people inundated with fast food, and helping the planet by reducing “food miles” — the distance food travels, and the energy that process consumes, to get to your plate.

Some research suggests the rise of farmer’s markets and community-supported agriculture (CSA) programs, in which farmers regularly deliver food to consumers’ doorsteps, has helped to improve the health of those who patronize them, and can benefit local agricultural economies. But a primarily local-based diet is still rare in the US; local food accounts for only around 1.5 percent of total US food sales.

Though the food movement isn’t nearly as focused on localism as it once was, one of its refrains — that reducing food miles is an effective way to fight climate change — has penetrated public consciousness. Nearly two-thirds of Americans believe eating local food is better for the environment than eating food produced from afar, according to a recent survey from Purdue University.

There’s just one problem: it isn’t necessarily true.

“It doesn’t have a major impact on greenhouse gas emissions to have a shorter distance between the farmer and the consumer,” says Laura Enthoven, a PhD researcher at the Université Catholique de Louvain in Belgium, who last year published (with co-author Goedele Van den Broeck) a review of common claims made about local food systems.

Going the distance

A few years into the emergence of the local food movement, environmental researchers began to investigate the real impact of food miles. In 2008, a paper published in Environmental Science & Technology found that transportation accounted for only 11 percent of food’s carbon footprint. Later studies pegged it as low as 5 percent in the US and 6 percent in Europe.

That’s because the main determinant of any given food’s environmental footprint isn’t how far it had to travel to get to your plate, but what kind of food it is — and specifically whether or not it came from an animal.

Farmed animals generate far higher amounts of the greenhouse gases methane and nitrous oxide through cow burps and animal manure than does the production of fruits, vegetables, nuts, plant-based meats, grains, and legumes. Raising animals for food also requires a lot more room than growing plants directly for human consumption, due to the massive amounts of land used for putting animals on pasture and rangelands and to grow the heavily subsidized and polluting corn and soy fed to farmed animals.

According to a Bloomberg analysis, “41 percent of U.S. land in the contiguous states revolves around livestock.” This represents a major “carbon opportunity cost,” as some of that land could be reforested to sequester carbon — but not if meat consumption keeps rising.

Greenhouse gas emissions from transportation, as well as processing, packaging, and refrigeration at the retail stage, are all minuscule compared to emissions caused by what happens on the farm — and that’s true no matter how close that farm is located to consumers.

For example, less than 1 percent of emissions from beef — the most emissions-intensive food of all — come from transportation, with nearly all other emissions coming from methane-rich cow burps and growing animal feed.

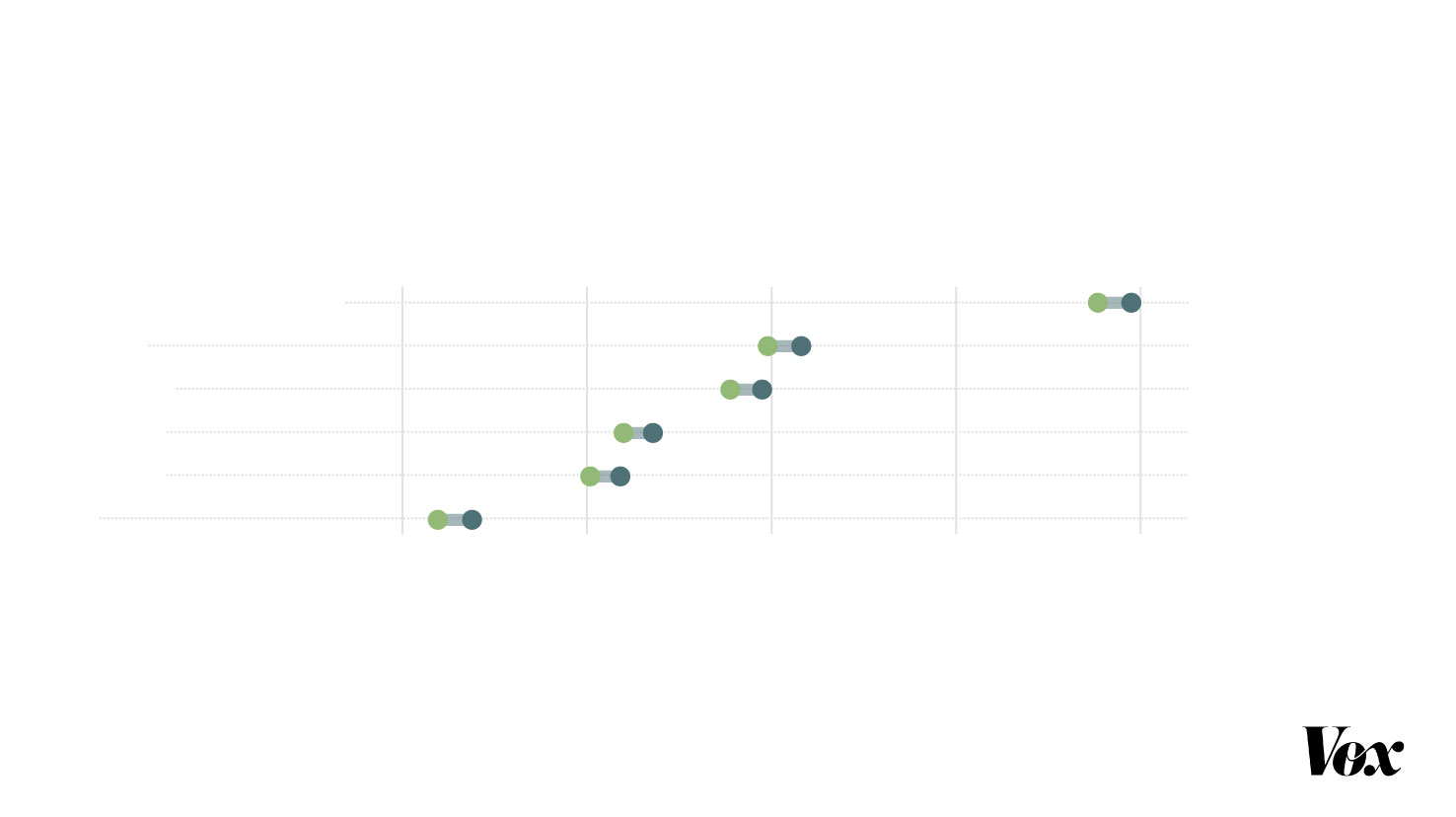

The chart below shows how eliminating food miles from several types of diets does little to reduce dietary greenhouse gas emissions. Instead, the amount of animal products in a diet largely determines its carbon footprint.

What we eat — not how far it traveled to our plate — determines

our dietary carbon footprint

Daily emissions of greenhouse gases from a variety of diets, in pounds of CO2 equivalents.

Daily emissions after eliminating

transportation emissions

Daily

emissions

|

|

-3.6%

-3.6%

Standard American diet

-5.7%

Half-vegan

-5.7%

-5.8%

-5.8%

No red meat

-6.7%

-6.7%

Pescatarian

-7.4%

-7.4%

Vegetarian

-13.3%

Vegan

-13.3%

5

10

15

20

25

The standard American diet is calculated from the USDA data on food availability and consumption. The half-vegan diet

cuts meat and dairy products from the standard American diet by half. A diet without red meat replaces red meat with

poultry and seafood products.

Chart: Youyou Zhou/ Vox • Source: USDA, Poore and Nemecek (2018), Vox

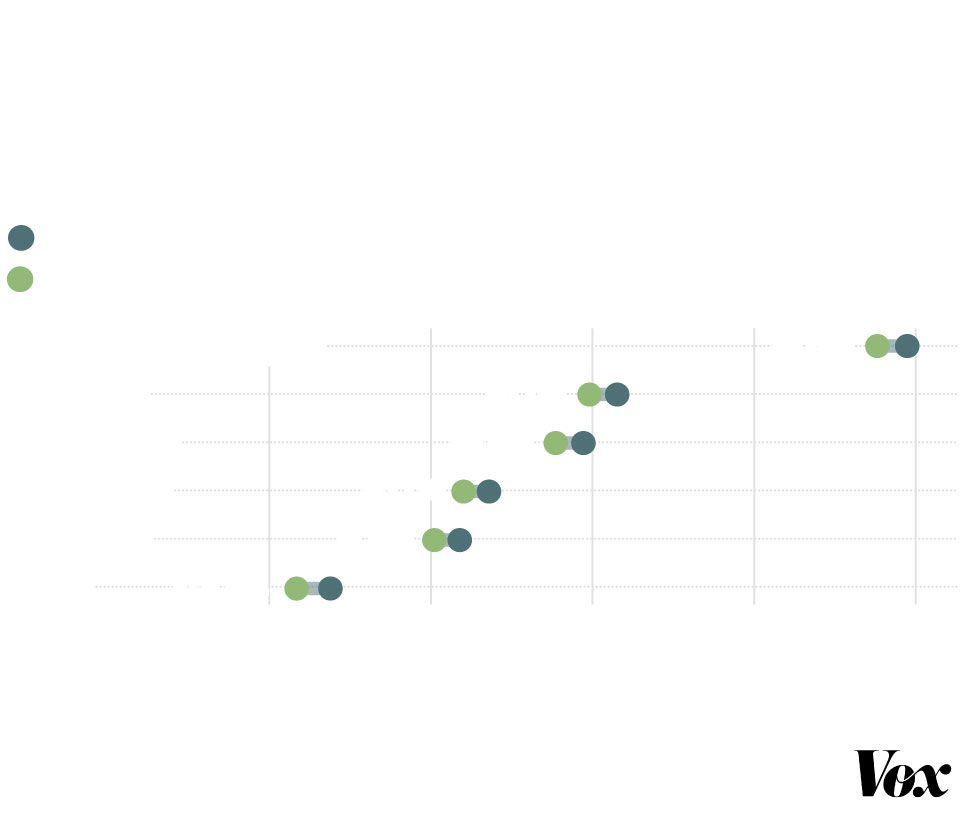

What we eat — not how far it traveled to

our plate — determines our dietary carbon footprint

Daily emissions of greenhouse gases from a variety of diets, in

pounds of CO2 equivalents.

Daily emissions

Daily emissions after eliminating transportation emissions

-3.6%

Standard American diet

-5.7%

Half-vegan

-5.8%

No red meat

-6.7%

Pescatarian

-7.4%

Vegetarian

Vegan

-13.3%

5

10

15

20

25

The standard American diet is calculated from the USDA data on food availability and

consumption. The half-vegan diet cuts meat and dairy products from the standard American

diet by half. A diet without red meat replaces red meat with poultry and seafood products.

Chart: Youyou Zhou/ Vox • Source: USDA, Poore and Nemecek (2018), Vox

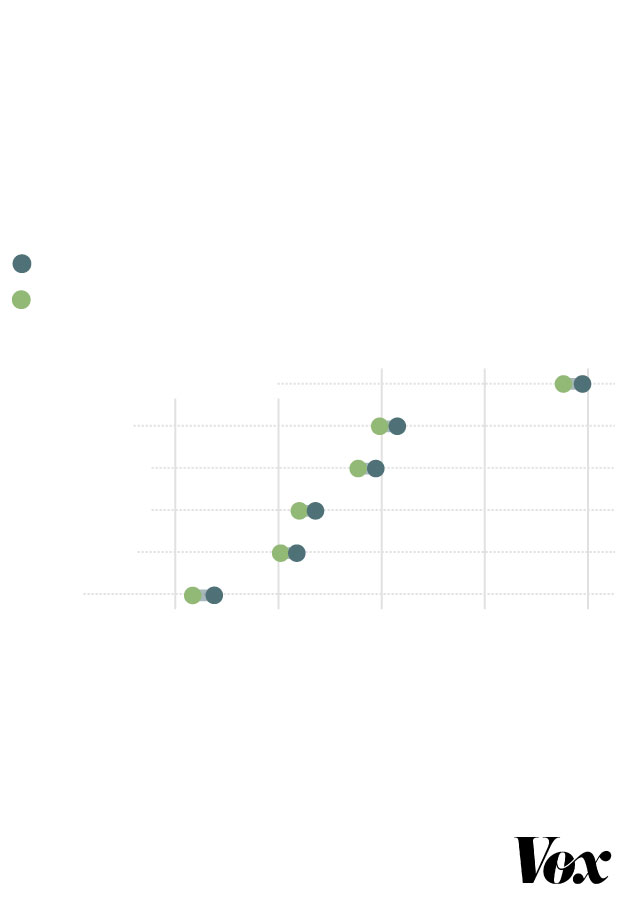

What we eat — not how far it

traveled to our plate — determines

our dietary carbon footprint

Daily emissions of greenhouse gases from a

variety of diets, in pounds of CO2 equivalents.

Daily emissions

Daily emissions after eliminating transportation

emissions

Standard American diet

-3.6%

-3.6%

-5.7%

Half-vegan

-5.7%

-5.8%

No red meat

-5.8%

-6.7%

Pescatarian

-6.7%

Vegetarian

-7.4%

-7.4%

Vegan

-13.3%

-13.3%

5

10

15

20

25

The standard American diet is calculated from the USDA

data on food availability and consumption. The half-vegan

diet cuts meat and dairy products from the standard

American diet by half. A diet without red meat replaces

red meat with poultry and seafood products.

Chart: Youyou Zhou/ Vox

Source: USDA, Poore and Nemecek (2018), Vox

Purchasing locally produced food comes with transportation emissions too, but the point of the chart is to illustrate the small role they play, no matter where the food was produced. However, most Americans apparently believe eating local is inherently better for the environment.

According to recent surveys conducted at Purdue University, nearly two-thirds of both urban and rural Americans believe that eating local food is better for the environment, while just a little over half of urbanites and 39 percent of rural residents believe eating less meat is good for the environment. Americans are also much more likely to choose local foods over non-local foods than they are to choose plant-based proteins over animal proteins.

But people can do both. And just reducing meat, milk, and egg consumption won’t be enough to meet Paris climate agreement targets; according to Hannah Ritchie of Our World in Data, reducing food waste, improving crop yields, and elevating on-farm practices (like fertilizer management) would go a long way toward slashing agricultural emissions. But a shift toward plant-rich diets would do more than any other single change.

While greenhouse gas emissions are just one aspect of environmental impact, there’s also water pollution and farmworker health issues caused by chemical fertilizers and pesticides. But as of the most recent data in 2012, farms that sell through farmer’s markets and CSA programs use these inputs at comparable rates to farms that don’t.

Put another way, it’s a farm’s practices — and what it produces — rather than its size or location that most determine its effects on the environment, not to mention the impacts on farmworkers and animals.

What we know about local food systems

Despite the scientific consensus that food miles are largely inconsequential in shrinking America’s agricultural emissions, and how little farm proximity tells us about the ethics of any given farm or food item, purchasing more food grown close to home can still reap some benefits.

“I don’t ever like to say, ‘Well, only 5 percent of emissions are transportation, so local food doesn’t make any sense,’” Christine Costello, assistant professor of agricultural and biological engineering at Penn State University, told me. “Localized foods can provide more diverse foodstuffs for people, more access to produce, more access to more quality foods … and then potentially it can stimulate economies.”

Enthoven, of UCLouvain in Belgium, has studied common claims around local food in detail and found that there are some benefits to be reaped from buying food grown close to home, but cautions that most of the research is correlative, so disentangling the effects of local food systems is often difficult.

The first benefit is that access to farmer’s markets and CSAs is correlated with increases in vegetable consumption, fewer meals eaten at restaurants, less consumption of processed food, and lower rates of obesity and diabetes. However, these benefits — some of which are self-reported — have largely gone to higher-income consumers, though CSAs and federal and state policymakers have made progress in making CSAs and farmers markets more accessible to low-income consumers in recent years.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23577717/GettyImages_1315193316.jpg)

Some research also suggests that local food systems can benefit a region’s agricultural economy and generate more jobs, but it’s far from clear whether purchasing more local food reliably increases small farmers’ income. While farmers who sell in short supply chains can sometimes see a boost to their income, income can also fall, in large part due to the time and labor required to sell at farmers markets and through CSA programs.

Stacey Botsford, who grows vegetables and raises a small number of animals at Red Door Family Farm in Athens, Wisconsin, told me diversification is critical to her business.

“I’m not making as much money [through wholesale] because there’s a middleman, but I’m not doing as much work,” she said. “The farmers market is where I make the most per unit, but if people don’t come [due to rain], you don’t make that money. Being diversified helps with that a lot — it’s like the stock market ... you want to spread it out a little bit.”

Tess Romanski of the Fairshare CSA Coalition in Madison, Wisconsin, notes that farmers and consumers get involved in local food systems to improve the kind of social ties that can decay in an age of fast food and mass retailers. Consumers’ desire to have a connection to their food only accelerated during the pandemic and its supply chain disruptions, Botsford says. “People are becoming a lot more aware that food systems are fragile and that they matter a lot. We sold out our CSA this year faster than ever before.”

But farms like Botsford’s will always be at a disadvantage so long as US agriculture policy heavily favors corn and soy production used primarily for inefficient biofuels and animal feed. And localized food systems will always be constrained for “economic, logistic, topographical and even arithmetic reasons,” according to Washington Post food columnist Tamar Haspel, herself a farmer.

In a 2017 article, Haspel explained that fresh local food is highly seasonal, especially in colder Northeastern climates, where nearly 20 percent of the US population lives, while much of the contemporary American diet relies on staple crops grown at scale in a few regions, then stored and consumed months or even years later elsewhere.

Haspel notes that some of the densest parts of the US, like the Northeast, have little cropland, whereas “the northern plains (the Dakotas, Kansas, and Nebraska) have 24 percent of the land but 2 percent of the population.”

And it shouldn’t be assumed that laborers who pick the food or manage or slaughter the animals in local food systems are inherently treated better. Farming operations that utilize fewer than 500 “man days” — a day in which an employee works for at least an hour — are exempt from paying the federal minimum wage, and farms that employ fewer than 10 people are exempt from OSHA safety oversight and investigations (though a few key states earnestly fill this gap).

Farmworker advocates and researchers report widespread health and safety issues across agriculture, as farm work ranks as one of the more dangerous occupations in the US. Each farm is different, but the appeal of locally produced food shouldn’t obscure these problems where they occur.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23577728/GettyImages_590630641.jpg)

The same goes for animal welfare. Small farms are less likely to use the most viscerally disturbing hallmarks of factory farming, such as tiny cages and crates, but aren’t immune from allegations of neglect and welfare concerns either.

Putting more of our food dollars into local food systems will do little to shrink America’s dietary carbon footprint. But one legacy of the local food movement — which has been largely supplanted by calls for “regenerative” farming, an approach focused on soil health and land management — is that it created a level of interest in improving the food economy that adjacent movements, like those for public health and animal welfare, haven’t been able to achieve.

But its limits underscore a hard truth about the fight for a more sustainable food system: Solutions that may intuitively feel as though they’re good for the climate, like shortening the distance between the farm and the table, may not actually be so. To tackle that biggest of environmental challenges, we’ll need to rethink our personal and political relationship to meat, not just our distance to the farm.